House History

21 Chester Place

The mystery behind “The Real Addams Family House”

Construction began on this house in the autumn of 1887, for Henry Gregory Newhall, and was officially listed in the 1888 Los Angeles City Directory off of Adams Street, just west of Figueroa St., in Los Angeles, California. Built in what is today called the West Adams District, just southwest of downtown, it was located in one of the oldest neighborhoods in Los Angeles, with most buildings being erected between 1880-1925.

The area started with a Los Angeles land survey conducted in 1853, by Henry Hancock (a Harvard trained lawyer and land surveyor working in California in the 1850’s). In between what was briefly designated for a few years as boulevards (which were just dirt roads back then), were large 35-acre land lots that became available for purchase after the land survey. In 1855 he purchased for himself one of the lots on the northwest corner of Adams and Figueroa St., and then eventually he sold the 35-acre lot to investors in 1876.

A New England sea captain, Nathan Randolph Vail, purchased a portion of that land off of Adams Street on July 26, 1876, to build a home for his own use (which would later become the gated community Chester Place). During this time, or possibly sometime later, the Newhall family also acquired a portion of Hancock’s acreage off of Adams Street, although I don’t believe that the Newhall’s did anything with the land at that time.

On November 5, 1885, Nathan Vail sold the land and his home on Adams Street to retired Arizona Federal Judge, Charles Silent. By November 1887, with St. James Park coming to a completion nearby (a patch of land developed for a residential park), plans were already underway to build Henry Gregory Newhall’s house, and construction began close to St. James Park and Charles Silent’s land on Adams Street.

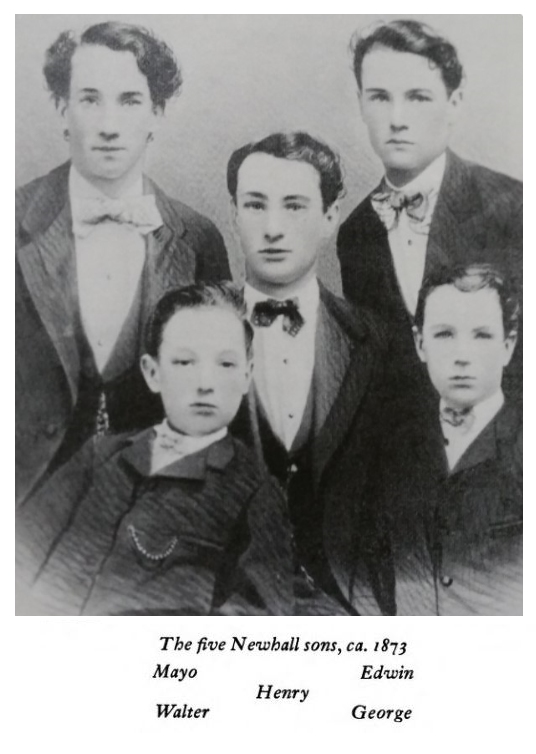

When Henry G. Newhall’s father died in 1882, wealthy businessman Henry Mayo Newhall (whose extensive land holdings became the Southern California communities of Newhall, Saugus, Valencia, and the city of Santa Clarita), the Newhall brothers with their inheritance the following year, developed The Newhall Land and Farming Company (based in San Francisco).

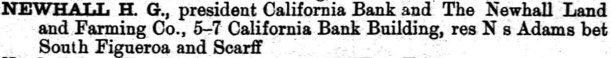

Henry, being the eldest, was made president of the company and during a directors vote to divide up the ranch properties that the family owned, was assigned active supervision of the land that was once known as Rancho San Francisco (located within Los Angeles county). In 1887, after also becoming the president of the new California Bank, Henry decided to relocate his family (his wife Mary Wyatt Newhall, and their one-year old daughter Alice), from San Francisco to Los Angeles; which made it more convenient to manage Rancho San Francisco, since it was located just northwest of Los Angeles.

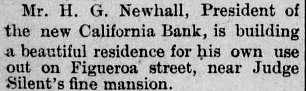

Since the Newhall house was being built somewhat farther back on their land, away from the nearest surrounding streets, an early Los Angeles Herald ad on November 3, 1887, originally announced that Mr. H. G. Newhall was building his residence out on Figueroa Street. Although when Henry’s house was completed and listed in the Los Angeles City Directory in 1888, it was officially designated as being on Adams Street (located in between St. James Park and Charles Silent’s land).

The zanja system, a series of irrigation canals that brought water from the Los Angeles River to a dam upstream, brought water down Figueroa Street to Adams Street (with an extension ditch that was added that also brought water westward along the south side of Adams Street), and then south to Agricultural Park, created a fertile area with an abundance in water.

The Streetcar line that ran south on Main Street, then west on Washington Blvd. to Figueroa Street, and then south to Agricultural Park, also made it convenient to travel to the Adams District. Due in part to these factors the wealthy flocked to this area during the very late 1890’s and early 1900’s, and many grand homes were erected during that time. The Adams District ended up becoming one of the most desired and wealthiest districts in the city, with massive Victorian mansions.

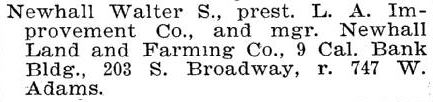

With the house being situated quite some distance off of Adams Street and new homes were being built in the immediate area, it caused the house to have multiple addresses throughout the years. In the very beginning between 1888-1890, the Los Angeles City Directory listed the house address as “N s Adams bet South Figueroa and Scarff” (which is more like a location instead of an actual address). By 1894 though, with Adams Street now divided into west and east, the Los Angeles City Directory list the address for the Newhall house as 747 West Adams St.

With most of the Newhall brothers married with large families by this time, the income that allowed their father and mother to live in luxury did not seem to meet the demands of five families wanting to continue to live that same lifestyle. It was also discovered that some of the ranches that the brothers owned had been slowly draining the family purse, instead of increasing their profits, due to a national economic slump, so the brothers did try to sell some portions of their inherited land and stock around this time to pay back some debt owed by the family (most of them were able to adjust financially).

Reports are that Henry had accumulated so much personal debt around this time though, that he sold most of his stock to other members of the family; borrowed on the rest, and moved his family overseas to their English cottage (although he still held the title as company president for a few years). One of Henry’s brothers moved into the house at this time and officially took over managing Rancho San Francisco.

After a few years Henry and his family (wife and three kids; Alice, Donald and Leila), did return to the States and he went back to work for the family business as an engineer and surveyor (a position that was far more to his liking than the details of administration, since he had studied surveying at Yale). William Mayo Newhall (the second-oldest brother, who went by his middle name Mayo), succeeded Henry as president.

Walter Scott Newhall (the fourth-eldest), on September 22, 1896, married Nellie Trowbridge Ainsworth. I can only speculate since this is not a known fact, but there is a possibility that Henry gave the house to his brother Walter S. Newhall as a wedding gift for the bride and groom. Walter had been living in the house while Henry was in England, so that he could be close to Rancho San Francisco (which was now his responsibility), and it just made sense for Walter to continue to live there as he had been.

Whether the house was a wedding gift for his brother and his new sister-in-law, or if Henry actually sold the property to Walter because he needed the money, is truly only speculation (truth is we will probably never know for certain). Nevertheless, from this point on Walter Scott Newhall is listed as the owner of the house at 747 West Adams St.

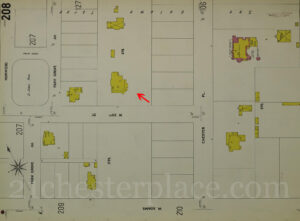

When the gated community Chester Place, that runs north to south between West 23rd Street and West Adams Street (with gateways at both entrances), was created and subdivided on Charles Silent’s land in 1899, another street was made to connect Chester Place to St. James Park. Since that land where the new connecting street would be placed belonged to the Newhall’s, I speculate that this is when Charles Silent purchased the land from Walter that stretched from Walter’s house to Adams Street. The new street ran right in front of the Newhall home, therefore, giving the house again, a new address of 735 West 25th St. (although not for long).

The Doheny’s, Oil tycoon Edward & Estelle Doheny, purchased 8 Chester Place in 1901, and subsequently started buying up the remaining lots in Chester Place to control and ensure their privacy (eventually acquiring all of Chester Place from Charles Silent).

Between the 1901 and 1902 Los Angeles City Directories, the small portion of West 25th St. that ran right in front of the house was renamed Chester Place. Since the Newhall house and the land that it actually sat on didn’t belong to Charles Silent or the Doheny’s, the house was not actually considered apart of Chester Place. However, I speculate that due to the Doheny’s influence and the fact that the land that stretched from Adams Street to the house did not belong to the Newhall’s anymore, the portion of the street right in front of the house was renamed starting in 1902, and the house address did change to 21 Chester Place during this time.

Although the Newhall’s wanted a family of their own, it looks as if they did not attempt to have anymore children after a stillborn birth during the first year of their marriage. In March 1902, Walter placed an ad in the Los Angeles Herald announcing that the Newhall’s were looking to hire a woman part-time to help with a family of four at his residence. It seems that during this time Nellie’s sister Bessie, and her son Edwin, came to live with Walter and Nellie (the house was certainly large enough), and on October 7, 1903, Bessie got married in an intimate but lavish wedding at 21 Chester Place. After their honeymoon in San Francisco, the newlyweds Mr. and Mrs. Foxton moved to Riverside, California.

Walter Scott Newhall, by all accounts, was a good-natured hard working family-oriented man, that was well liked among his peers. I think it is safe to say as well that the Newhall’s were also very well known among the city’s most social elite (with Walter serving as president of The California Club), and the house did seem to be loved and cherished in its heyday by Mr. and Mrs. Newhall. A good reflection of this is seen throughout the years in many Los Angeles Herald announcements, that the Newhall’s proudly used their house as a social stomping ground for luncheons and dinner parties; usually at Mrs. Newhall’s request.

Reports are that as early as April 1906, Walter did begin to feel ill. Still not feeling well by the end of October, he decided to take some time off work and took Nellie to Europe for a vacation to try and recuperate. After only a week or two in England with his health worsening, doctors advised the Newhall’s to return home. Unfortunately, Walter did not get better and on Christmas Day 1906, at the age of 46, Walter died at Adler’s Sanitarium in San Francisco. He was buried in the Newhall Family Plot, which had just been moved to Colma, California, at Cypress Lawn Memorial in 1901 (due to the San Francisco ban on cemeteries and burials). He was not only preceded in death by his son, Walter Trowbridge Newhall, his parents and an aunt, but his eldest brother Henry as well; whom passed away in 1903, at the age of 50.

Although I have not been able to find much information on Walter’s wife, Nellie, I have discovered that her full name is Nellie Hammill Trowbridge (Trowbridge is her Maiden name), and that she was married before her marriage to Walter to a man named Dr. Frank Ainsworth (which is why her name is listed as Nellie Trowbridge Ainsworth, when she married Walter in 1896).

According to the Los Angeles City Directory, Nellie was still living in the house by 1908. Just two years later though in June 1910, her late husband’s estate was sued for back loans and interest that Walter had acquired in advance on promissory notes about a year before he died. His younger brother, George A. Newhall, who was now the president of the family company, claimed the amount was justly due; therefore, Nellie had to fork over $86,025.00 (which is equivalent to nearly $2 million dollars today).

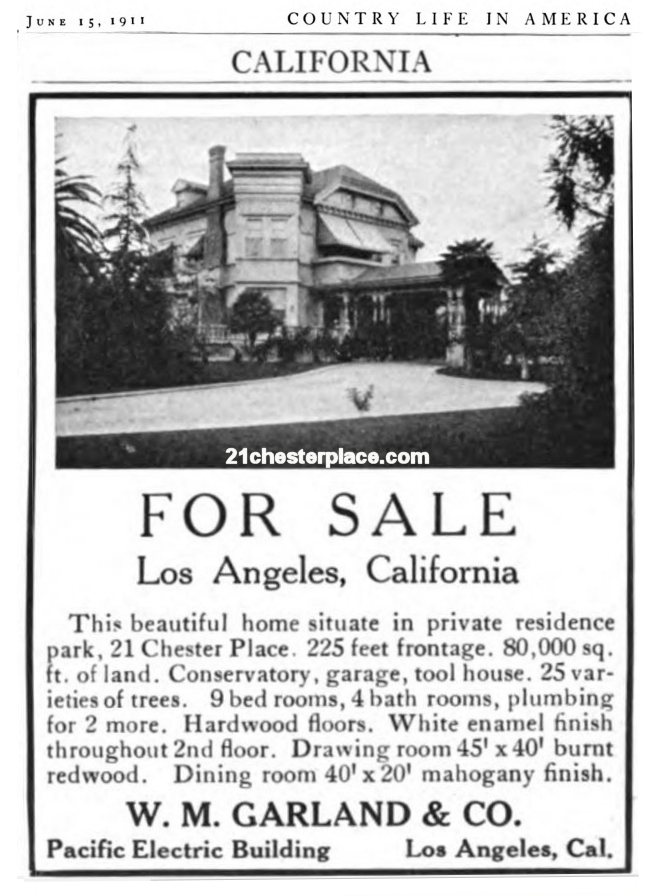

Taking that into consideration I speculate that is why Nellie hired W. M. Garland & Co., to sell 21 Chester Place (completely furnished), and the house and land went up for sale in 1911. Within just ten months after the Newhall estate was sued, Nellie married U.S. Navy Captain Charles H. Harlow; sold the Newhall property in April, and then shortly thereafter moved east with her new husband.

It should be to no one’s surprise that the house was not on the market for very long. In fact by the time the ad for the house was finally featured in June, in Country life in America, the Newhall property had already been purchased by newlyweds Gorham Tufts Jr., and his new millionaire widow bride Jane Henry “Jenny” Scranton-Roe. They moved into 21 Chester Place in April 1911, with Gorham’s sons from a previous marriage (Warren 12, Fletcher 10).

When Mrs. Roe’s first husband died in December 1909 (Fort Worth, Texas, lumber millionaire, A. J. Roe), his mass fortune was bequeathed to his wife and three daughters. Mrs. Roe (with the youngest of the three daughters now off to college), who had long been a worker in the Christian Science Church (in Fort Worth), attended a Christian science convention in California, where she was reintroduced to a man named Gorham Tufts, Jr. (the two had previously met at a convention in Dallas, Texas).

Mr. Tufts considered himself a traveling evangelist who had traveled far and wide, from city to city, giving discourses on religion at church meetings or conventions, and sharing his experiences as a missionary in India. By 1910, he was living in California where he had amassed a small group of followers that were listed as “missionaries” (most of them were women).

After being reacquainted at the convention, the two must have realized that they had a lot in common because after only a short period of time courting, millionaire lumber heiress Jenny H. S. Roe and Gorham Tufts Jr. got married, and purchased the Newhall property in April 1911. In the following month of May, the Tufts put an advertisement in the paper for an estate sale at their new home to sell the remaining Newhall furniture that came with the purchase of the house.

However, the honeymoon did not last long though. Just a month after they were married, Mr. Tufts tried to scam Jenny’s three daughters by tricking them into signing papers that would make their half of their late father’s inheritance community property; gaining access to the account as the spouse of the daughters’ remaining biological parent (which would have benefited him directly). Once the girls became aware of the trickery they called on a slew of lawyers to override and cancel those estate papers, and were successful in their quest in nullifying the paperwork. Mr. Tufts explained to his new wife and stepdaughters that lived out-of-state, that it was just a misunderstanding and all seemed to be forgiven.

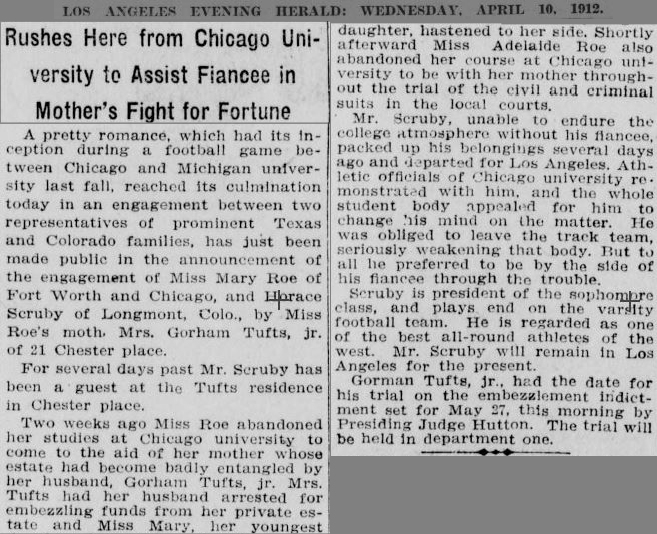

By March 1912 though, less than a year after they were married, Mrs. J. H. S. Roe-Tufts had revoked all powers of attorney granted to him and filed for a divorce. She also hired a lawyer and sued her husband on charges of embezzlement. Tufts was jailed in Los Angeles, and charged with embezzling $100,000.00 from the Roe estate. Around this time, Mrs. Roe-Tufts youngest daughter, Miss Mary Roe, left college to travel to Los Angeles to be at her mother’s side for support. During those few months that Mary Roe was living with her mother (during the spring of 1912), she also became engaged to and married her college sweetheart at 21 Chester Place.

During the month of April, with Mr. Tufts still in jail unable to afford bond, more women began to surface who had been members of his missionary trip to India; claiming that they had also lost “property, attire, money and jewels as a result of their trust in Mr. Tufts.” A grand jury was then formed to also investigate Tufts financial transactions, in connection with his alleged missionary efforts.

The worst was still yet to come though for Mr. Tufts, when his first wife Mrs. Mary Tufts surfaced and declared that she had never abandoned her husband and their children like Gorham had declared; in fact, he had abandoned her by putting her in a mental institution overseas and returning to the States with their two kids (without her knowledge or consent).

She told the court that after they were married in Chicago in 1895, the missionary couple then went to India with his “followers” in tow and established what she called a “pseudo school of philosophy” (where Tufts had proclaimed himself to be “The Love God”). She stated that while they were in India he had been abusing her. He eventually deserted her to return to Chicago with their sons, and then divorced her without her knowledge with claims that she had deserted him.

She asked the court to release and grant her custody of their two sons and informed the court that she had already filed with the court in Cook county, Illinois, to have the divorce granted to Mr. Tufts revoked (under grounds that it was obtained by misrepresentation), so that she could divorce him instead (which the court did eventually do for her).

When Mrs. Mary Tufts finally got to see her kids during juvenile court in the presence of probation officers, she wept as she embraced her boys for the first time in six years. Her sons told the judge that they were startled when they saw her, because they had been told that their mother had died. The two Mrs. Tufts (wife number one and wife number two), agreed to help each other in their legal battles against their husband.

Gorham Tufts Jr. was found guilty of fraudulently obtaining money from his second wife Jenny in July 1912, and was sentenced to three years in San Quentin prison; the sentence was imposed after Mr. Tufts pleaded for probation. As the months followed after the trial, more women continued to surface claiming that he took advantage of them financially.

In October, Mrs. Jenny H. S. Roe-Tufts petitioned the Los Angeles Superior Court for permission to drop the last name Tufts; declaring that it would be harmful to her for the management of her affairs, reciting her recent suit against Tufts on a charge of embezzling a part of her large estate (she also alleges humiliation through use of the name). Sure enough the following year in the 1913 Los Angeles City Directory, it does show that she had dropped the name Tufts.

On March 2, 1914 (after a successful appeal), Gorham Tufts Jr. was released from prison. When asked where he planned on going now that he was a free man, he stated that he was immediately heading to New York in hope of a reconciliation with his second wife Mrs. Jenny H. S. Roe (who had recently relocated to the east coast). Believe it or not they were still married because when the court revoked Mr. Tufts first divorce, at Mary Tufts request (so that she could divorce him), it left Jenny and Gorham’s marriage in limbo until the first divorce was eventually finalized. Once the divorce to his first wife was finally finalized though, Jenny did not continue with the divorce because by July 1913, Jenny now believed that her husband had been set up.

A newspaper article dated April 2, 1914 (one month after Gorham’s release from prison), revealed that the two had reconciled and that Mrs. Jenny H. S. Roe-Tufts would give her husband a half-interest in her California and Texas estates. As the year progressed Mr. and Mrs. Tufts continued to claim to the newspapers that they had been set up all along by trusted associates who were out to frame and ruin Mr. Tufts good name, and in the process try and extract as much money from Mrs. Tufts as possible. She proclaimed that she would spend the rest of her fortune if need be, to clear and restore her husbands name.

The couple made it in the newspapers a few more times in the following years with much of the same claim, before disappearing from the public eye. What transpired during their relationship the last few years of Jenny’s life would only be speculation at this point; for when she died on January 18, 1918, in Fort Worth, Texas, she was laid to rest next to her first husband, A. J. Roe, with no mention of the name Tufts on her grave.

When the newly reconciled Tufts sold 21 Chester Place in 1914 (shortly after the Chicago Examiner article in April), they sold the house and land to none other than Estelle Doheny herself. Estelle then had a set of gates placed on the street to enclose the house (as well as two houses across the street from the Newhall home), within Chester Place; whereupon, the Newhall house was then officially included as part of the gated community (although most people in the neighborhood probably already assumed it was). It then became a rental, as Estelle had done with the other houses that she had acquired in the surrounding area. She obviously did not waste much time because by 1915, the house did have its first rental occupants.

In most cases with rental homes you would assume that there would be a lot of different occupants throughout a fifty-two year rental history, but that was not the case with 21 Chester Place though. Between 1915 and 1967, only two sets of renters got the great privilege of calling 21 Chester Place home.

In the 1915 Los Angeles City Directory it does show that a James H. Adams (abbreviated as Jas H Adams), was occupying 21 Chester Place. He and his wife Lillian (and son Morgan), must have loved the house because the directory shows that they lived there for at least 17 years. Like the Newhall’s they were also social butterflies. They gave dinner parties and hosted banquets, making the gossip columns in the papers quite frequently for years while living in the house.

The Los Angeles Herald announced the wedding of Mr. and Mrs. Adams’ son, Morgan Adams, and his new bride Aileen McCarthy, in February 1915. The article states that after their honeymoon they would return home on March 1st to their many friends, at 21 Chester Place. While living there at the house Morgan and Aileen welcomed their first child in August 1915, Morgan Adams Jr., and their second son, James ‘Peter’ H. Adams II, in 1917.

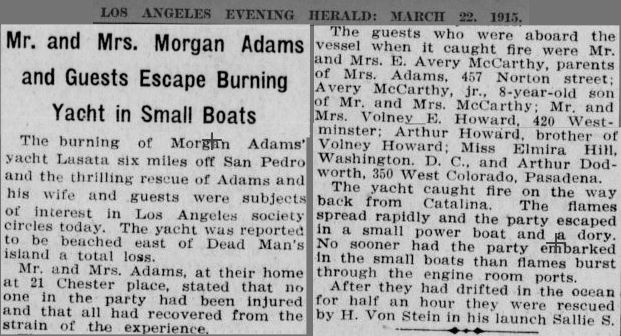

Just like his parents, Morgan Adams was in the papers quite frequently (although he was much more outdoorsy). He made the papers in March 1915, when his yacht caught fire off Catalina Island; carrying not only he and his wife, but family and friends as well. The article states that “no sooner had the party embarked in small boats, flames burst through the engine room ports.” They drifted in the ocean for half an hour before being rescued by H. Von Stein, in his launch Sallie S (thankfully, no one was hurt during the ordeal).

With his love for sailing, Morgan made the papers again in May 1915. This time he broke the sailing yacht record with his yacht Nixie. The article states that “Morgan Adams, 21 Chester Place, has established a new record for a sailing trip down the coast”, when making the trip from San Francisco to Los Angeles harbor, on a sailing yacht in just forty-nine hours (with the company of four friends no less).

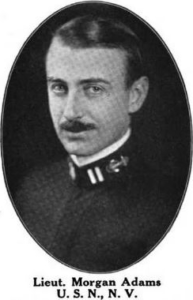

Because of his love for the sea, Morgan Adams joined the California Naval Militia in 1913 (a counterpart to the National Guard), and having sailed nearly all over the globe as well as his knowledge and expertise with different types of marine engines, navigation and electricity, secured a position as Navigator of the Battleship OREGON (when on practice cruises). During World War I, after four years in the Naval Militia, Lieutenant Morgan Adams entered the service of the United States Government on April 6, 1917, as Commanding Officer of the Torpedo Boat FARRAGUT. In doing so, he became the first officer of the Naval Militia to be placed in command of a U.S. Navy vessel. In 1918, he advanced to the rank of lieutenant commander and was later placed in command of the Pacific terminal of the Panama Canal.

In 1921, Morgan and Aileen separated and divorced. In the following year, Morgan’s father, James H. Adams died. Although I am not for sure if Morgan still lived at 21 Chester Place during this time, his mother Lillian did continue to live in the house for another decade at least. Unfortunately, since there is not a Los Angeles City Directory for every year, the last year that I can confirm that Lillian Adams still lived in the house is in 1932.

The same probably could be said for the second and last set of renters as well, regarding their possible fondness towards the house. In the 1936 Los Angeles City Directory, a couple named Paul and Helen Grafe are listed as living in the house. Although I have not been able to find much information on the Grafe’s just yet, a U.S. Census taken on April 1, 1940 does show that there were seven people living in the house; Paul and Helen Grafe, their three daughters (Helen 13, Louise 10, Paula 8), a niece, and a cook.

In 1922, Paul Grafe joined W.E. Callahan Construction Company as a construction superintendent. After only just six years with the company he was promoted to manager, and by 1939 he had become the vice-president. W.E. Callahan retired from presidency of his company in 1943 , but remained as chairman of the board of directors until his death a year later. He was succeeded as president by Paul, and W.E. Callahan Construction Co. became The Grafe-Callahan Construction Co.

Paul and Helen Grafe purchased the Ferndale Ranch in Santa Paula, California, from Estelle Doheny in 1944, as their main homestead, and from that point on Paul used 21 Chester Place as his personal office for The Grafe-Callahan Construction Company. In multiple Los Angeles City Directories from 1956 to 1964, there are two phone lines listed for 21 Chester Place; Paul Grafe and a Mr. Richard T. Ramsey. Due to the success of The Grafe-Callahan Construction Co., I speculate that Mr. Ramsey worked for the company and was an associate of Paul Grafe.

The Grafe’s rented 21 Chester Place for at least 31 years until the city forced them out. They witnessed the transition from neighborhood to college campus in the early 60s, and were the occupants when Hollywood came a-knocking to use the house in a Motion Picture. Just a few months later, television producers came knocking on the door to use the house for a TV sitcom called “The Addams Family.”

Although 21 Chester Place was only used in “The Addams Family” 1964-66 TV show’s first episode (Season 1/Episode 1), for exterior footage of the house in the opening scene, you can also see the house porte-cochère in the background behind Gomez when he is filing the gates during the show intro (that is played before each episode). The house was also used in publicity photos for the show with John Astin (Gomez), standing in front of the house in different spots and poses.

However, the top portion of the house was not quite the look that they had imagined. Instead of constructing an actual full-scale front or shell of a home on a studio lot, they opted to use a matte painting of the house which could be altered for different scenes. To do this they hired an established optical effects studio, called the Howard Anderson Company.

They took a photograph of 21 Chester Place with some studio props added to make the house look a little dilapidated, and blew up the picture to a 30×40 inch black and white portrait. An artist named Louis McManus, brushed color oil paint over the photograph to add details and style to the house to make it exactly what they wanted. Using a technique with the matte painting placed over in-motion stock footage of the Newhall house, also gave them the ability to create an illusion of activity in front of “The Addams Family” home.

After filming stock footage of the house for use in the first episode, and taking the look of the house in general, they used the matte painting of “The Addams Family” house for the rest of the shows course. 21 Chester Place was also briefly used exterior-wise in the 1964 Motion Picture “Seven Days in May”, and in one episode of the 60’s TV sitcom “Hazel.”

Unfortunately the house is no longer standing though. Since the producers of the show didn’t need the house after they had captured all the footage they wanted from it, even if the show carried on for multiple seasons, it was not purchased and moved to a studio lot off of the land that was now owned by Mount St. Mary’s College, the Doheny Campus (now considered to be a University).

When Estelle Doheny died in 1958, she willed the land to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles; whom then gave the land to Mount St. Mary’s College, and in 1962 the college officially opened up a satellite campus at Chester Place incorporating most of the historic homes within student housing and teaching. Unfortunately the college let Paul and Helen Grafe continue as the rental occupants of the house (as they did with Blanche Seaver, who rented 20 Chester Place right across the street), so 21 Chester Place did not become an integral part of the campus.

The Newhall house survived for some time even as campus attendance rapidly increased within the first few years. Thankfully the house was still there in 1964, for “The Addams Family” producers to discover and use the house, but as soon as it seemed that the coast was clear (even after the Ahmanson Weingart Hall was built on campus in 1965, which houses an auditorium, classrooms and labs), the house that had once graced Adams St., West 25th St., and then became 21 Chester Place, was put on the chopping block in 1967; when the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Los Angeles, that owned the land that the house sat on, filed for a demolition permit to have the house and land cleared for a parking lot to accommodate the continued growth of the campus.

It was the only house on that side of the street that is now called St. James Park W, and the college wasn’t using the house (although it was still being occupied), so I guess they thought it was expendable. Obviously no one stepped up and tried to save this famous and historic house (although I speculate it wasn’t even put up ‘For Sale-to be moved’), so therefore it was shockingly demolished in 1967.

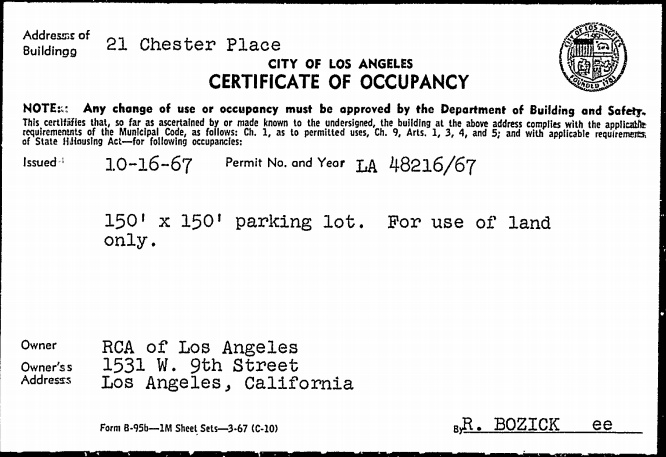

On June 9, 1967, the Department of Building and Safety issued a demolition permit for the house; notifying the Grafe’s to vacate within a certain time frame (usually thirty days from the notification date; sometimes more), and just eleven days later the permit to build a parking lot was filed. On October 16, 1967, just four months later, the ‘certificate of occupancy’ for the use of the new parking lot was issued (signifying that it was ready and could be used), so the house was demolished sometime between June 9th and October 16, 1967.

Although I am not quite certain just how long the campus used the land as a parking lot, but a 1972 aerial photo does give the impression that the college had by that time designated another parking spot for the campus; located across the street on the southwest corner lot, so that the Los Angeles Unified School District (L.A.U.S.D.), could build a High School at that location. Although for whatever reason they did not break ground to build the school until a decade later (possibly due to finances).

Sure enough in March 1981, the Los Angeles Times announced that a $5.9 million dollar contract to construct a new facility had been awarded and would be completed at that location in just 18 months (with most of the new construction financed from a state-earthquake safety bond issue). Now where the house once stood is a Track and Field, for the Frank D. Lanterman High School.

There is a ‘driveway approach’ on that side of the street still, but it is not the original one for 21 Chester Place. Unfortunately the original ‘driveway approach’ for the house was filled in and a new one, about 10-15 yards west from the original, was made for access to the parking lot that replaced the house, but is now being used for access to the Track and Field for the school.

Sadly the only thing left from the time the house actually stood there, on that side of the street inside the gates on St. James Park W, is the street itself (which has been repaved), portions of the sidewalk, and the six-globe street lamp that was installed close to the original driveway in 1903, which can be seen in some of the photographs of the house.

Continue to ‘Quick Facts‘